Sarah Bird

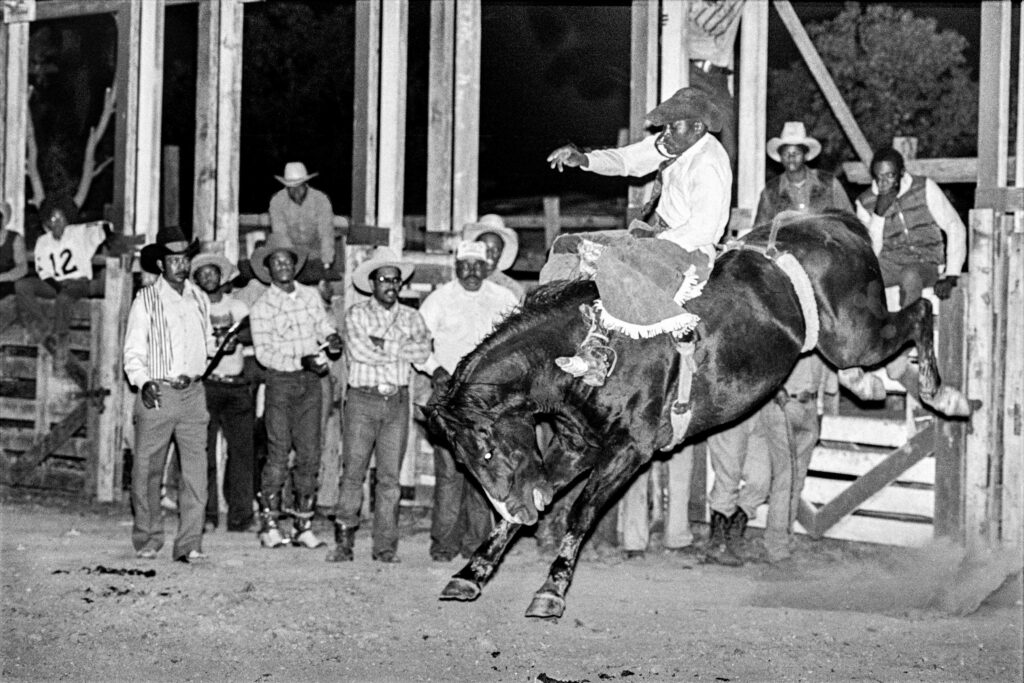

I’ve been on some exciting literary journeys with Sarah Bird. And now, Sarah has provided her readers with a new look into her arsenal of talent -- photography. During the languor of the pandemic, Sarah dug into a box of photos of Black rodeo contestants that she shot 40 years ago, along with notes she took along the way. She has turned this material into a remarkable book – Juneteenth Rodeo.

This book digs into the forgotten culture of Black men and women who engineered their own uber-competitive contests of riding and roping, with scant attention from the white world. Sarah tried to get a book or at least an article on this subject published over four decades ago. She futilely submitted proposals to a number of media outlets, but met rejection.

After that, she shoved the box full of photos and notes under her bed. It stayed there until 2020 when she donated her photo archives to the Southwestern Writers Collection where a gifted team of curators digitized the prints and negatives. Armed with the computer-based photos, she contacted The University of Texas Press. When they saw the shots and knew that Sarah would provide a world-class essay to go along with them, they greenlighted the project. Now all of us – finally! -- can have a look into this largely hidden part of Southwestern culture.

Recently, Sarah and I discussed how this book came to be.

- What was your original motivation to delve into this subject?

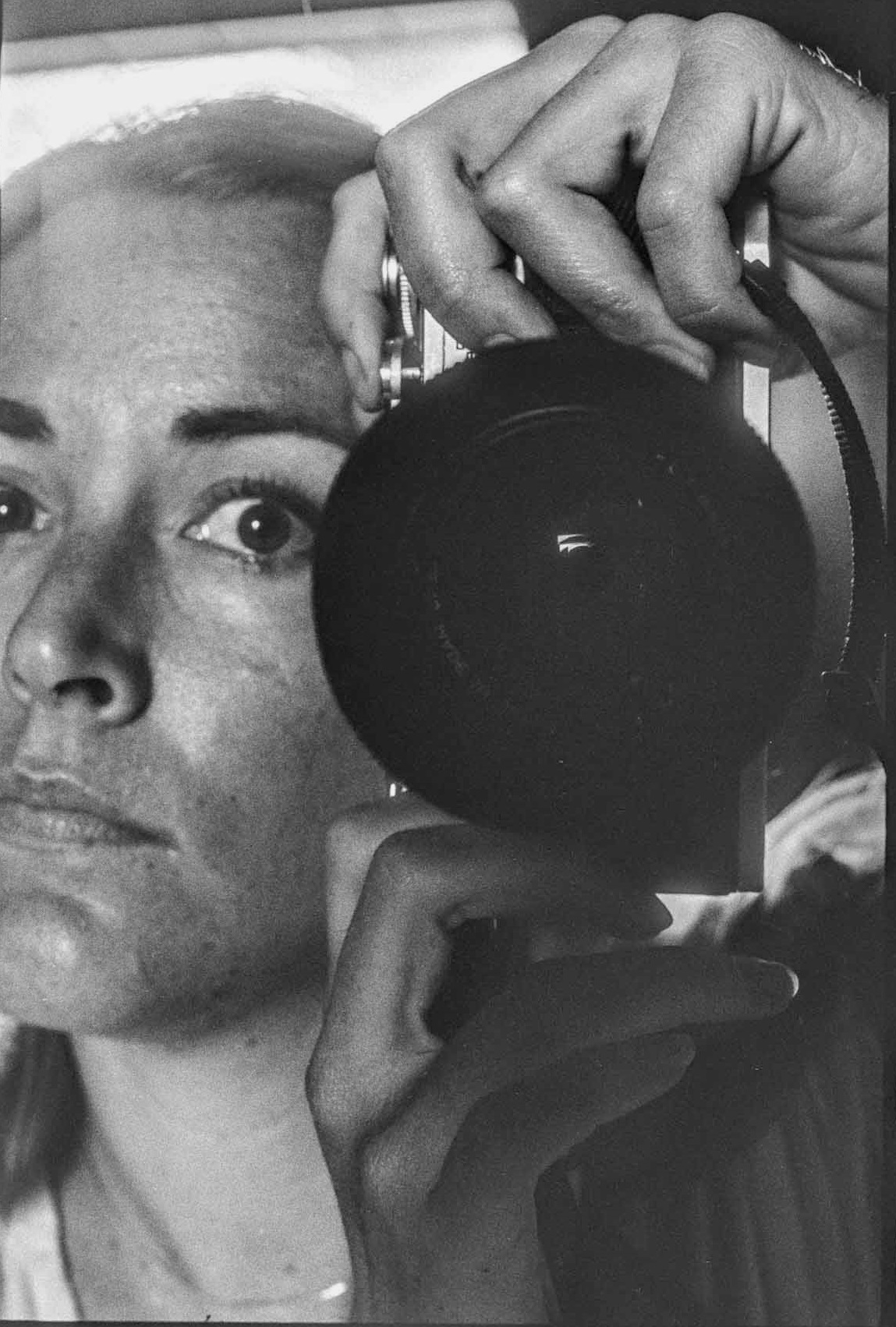

My decision to photograph Black rodeos was a function of my personality. As a pathologically shy military kid whose family was transferred way too much for her introverted nature, I became an observer. This inclination to watch and analyze my fellow humans predisposed me to pursue an undergraduate degree in Anthropology. When I won a fellowship to study at the University of Texas, I chose two of the observer’s other favorite fields: Journalism and Photojournalism.

As a newcomer to Texas, I was intrigued by, and photographed, rattlesnake round ups, sorority rushes, honky-tonk dance halls, and rodeos. Especially rodeos. As a child of the military, the only livestock I ever encountered growing up came in shrink-wrapped packages from the base commissary. What intrigued me was witnessing how each group remade this mainstream American pastime in their own image. How they created distinct cultures that orbited the arenas on their own unique trajectories. And the most distinct of them all were the Black rodeos.

- I had no idea that you are such an accomplished photographer. How did you acquire such extraordinary skills?

Whatever technical skills I had I credit to the two photojournalism classes that I took at UT. Beyond that, I pointed the camera at what interested me and what interested me most was how people are shaped by the group they aspire to be part of. How they adopt what anthropologists would call the “signifiers” of that group. And boy howdy, does rodeo, and Western culture in general, have a boatload of signifiers: boots, buckles, hats, dip cups, a way of speaking, and, even, of moving.

- How did you make your first inroads into this field?

I shot the 1974 Huntsville Prison Rodeo for a class assignment and never looked back. I was hooked on what I thought of as the “renegade rodeos,” the ones where competitors didn’t fit the mainstream definition of cowboy by not being a straight white male. I burned out the engine in my 1971 Vega Hatchback traveling to girls’, gays’, kids’, and old-timers’ rodeos. I captured charreadas along the border and Native American rodeos in Arizona and New Mexico.

I had never heard of Black rodeos until I went to a livestock auction in Clovis, NM in 1977 and a contractor there mentioned that he was bidding on bucking stock to take to Black rodeo at the Diamond “L” Arena.

- Where were the events you attended held?

The Diamond “L,” once a legendary venue for cowboys and girls of color used to be located on far south Main outside of Houston. All the other Black rodeos I documented were located in rural outposts like Plum, Egypt, Pin Oak, Bastrop, Hempstead, Spring, and Kendleton.

- Are you still in touch with any of your subjects?

The network definitely dissipated. Before I published the book I made it my mission to identify as many of my subjects as I could. I was dubious about social media for this purpose, but I tried. On Facebook and Instagram pages for Black Cowboys, Black Cowboy Events, Horse, Tack & More!!, and many others, I posted my photos and asked for help in identifying the cowboys, cowgirls, and their fans. Surprisingly, I started hearing from relatives and then the actual subjects of my photos. Randy McCullough was one such source. An award-winning veteran of the soul circuit, he was a gold mine of information. He seemed to have known, and even better, remembered nearly everyone in my photos. I could barely keep up as he reeled off names, nicknames—Dynamite, Blue, Skeet, Bo Pink--and anecdotes that brought all those formerly nameless faces to bright and vivid life.

The most exciting discovery was learning that I had captured several legends of Black rodeo. I had photos of the Jackie Robinson of rodeo, Myrtis Dightman, the first Black cowboy to be admitted into the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association. I identified Archie Wycoff who was featured alongside Muhammad Ali in the documentary “A Black Rodeo in Harlem.” I was delighted to learn that I had captured Taylor Hall, known to his fans as Bailey’s Prairie Kid, on one of his last rides before he retired from competition.

But the biggest thrill of them all was when The Kid, now 93 years old, made a surprise appearance at the opening of the photo exhibition that was funded through a grant from Humanities of Texas.

- Tell me about a couple of the most interesting people you met when you were doing your research.

Another of the legends was the great Rufus Green. Known as the Godfather of Black Rodeo, it was my great good fortune to meet him. Green earned the title as much for his majestic spirit and benevolent mentorship of a couple of generations of champion ropers as for his phenomenal roping skills. He followed Dightman to become among the first Black cowboys to cross the color line and earn membership in the PRCA. Like the other true, ranch-raised, old-school cowboys I met, Green had a soft-spoken, courtly manner. He was quick to laugh, slow to anger, and as Green’s close friend Monroe Lawson said, “he was incomparable in his disposition.”

He was certainly incomparable in his hospitality, allowing me to spend a couple of days with him at his home in Hempstead where I was privileged to watch his gentle way of training both young horses and young ropers. One memorable Sunday, Green invited me to join him for lunch. He held the restaurant door open and we stepped into what was obviously the after-church lunch spot for most of Hempstead. Conversation stopped dead and all eyes fixed on me. I was used to this reaction as it had happened at every small town Dairy Queen and country diner I’d ever set foot in on my travels. I was a stranger, a 5 foot 10 inch unaccompanied female one, at that. Stares were to be expected.

That time, however, the stares were for the unexpected sight of a Black man escorting a white woman into their midst. As he did with all things, Green navigated the scene with an easy graciousness he’d learned early. At the height of the Great Depression, a wealthy rancher from Victoria had spotted the young roping phenom and made Green’s father an offer: he would adopt the boy and “treat him like one of my own.” And that is what happened. I devote a fair amount of space in the book to Green’s story as he certainly was one of the most interesting people I met on what was called the Soul Circuit.

- How has the reception to your book been?

It has exceeded all my expectations -- stories in all the major Texas papers, radio and TV interviews, a grant from Humanities Texas to fund a traveling exhibition of the photos. But what has been most meaningful to me has been the reception from the communities where I photographed. So many of the children of my subjects and, in a few powerful cases the subjects themselves, have gotten in touch to express their gratitude.